Hello!

I arrived at a good stopping place on my new novel and took a minute to scroll social media. A friend posted a photo of Western North Carolina. The landscape jogged an old memory, and I wrote this little bit of first-person fiction.

"Johnny" Johnson

I ever tell you I lived in NC?

There was this one time my mother drove me out on the Blue Ridge Parkway to a McDonald’s near Little Switzerland to meet her biological father. A man who abandoned her when she was ten. About the same age I was then.

It was the first time they’d seen one another in thirty years. He was retired. Looked like any sixty-five year old to me. Bald head with liver spots. A little pale crust at the corners of his mouth. A tuft of white whiskers he'd failed to shave on the left side of his chin. I stared at that tuft when he spoke.

He gave me a ten dollar bill because I’d gotten a 4.0 on my report card. He patted my hand where it rested on the tabletop.

He told my mom he was writing spy novels after retiring from the Military. He’d been in intelligence, the OSS, which became the CIA. She once told me she remembered walking through the halls of the Pentagon, holding her father's hand. He was in his dress uniform. Lots of colorful pins on his chest. Every few steps someone would greet him, shake his hand, and he'd introduce her. She was in kindergarten, thought he was the most important man in the world. He was to her.

I ate an egg McMuffin while they whispered.

My mom cried.

I watched the snow.

We were there a while. My Mom got increasingly upset, used the weather as a reason to leave. As far as I know they never spoke again.

The thing that most impressed me was that the McDonalds was tucked in a lonely flat piece of ground around a switchback curve on a narrow stretch of mountain highway where you'd think nothing could be built.

The End.

I keep tinkering with this story. It keeps evolving. This version is how it sits for now. It may be a little different next week. But I find this kind of short fiction so so satisfying.

After spending more than a year on my current manuscript to get about 2/3 of the way through a first draft, writing a narrative I can see all on one page, hold the rhythms in my head from start to finish, is a breath of fresh air.

First-person feels right for this kind of short fiction. It reads diaristtcally, conversation, and casual. There's little need for character-building when the protagonist seems like it's me. I developed my love for these kinds of short, first-person stories at the Center for Book and Paper Arts at Columbia College, Chicago. I was playing with small zine-format books as a home for original narratives. How a story unfolds with the page-turns of a book, as the reader moves from one spread to the next, has continued to influence the way I construct stories. Because the zine-format is so short, I needed to find a quick way to establish a story and set up the turn and climax in as few words as possible. I stumbled upon first-person and immediately saw the potential in the tone to easily project emotional subtext in few words.

A note about the percentage of the story above that is fiction vs biographical: Some is true but intentionally composed for effect. Some is knowingly confabulated and warped by perspective and time. Some is just plain invention. For instance, I did not have a 4.0.

Novels are long projects. I can only focus on one scene at a time. But I have to hold the rest of the story in my awareness, somewhat out of focus, as context for each new section. It's only writing. I don't want to overstate it. But, it does make me exhausted.

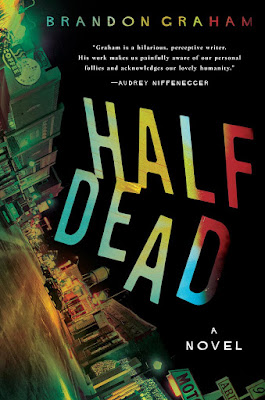

In book news: My first quarter sales report for Half Dead arrived. I want to thank everyone who bought it and read it and took a moment to send a note. Most everyone who reads these posts are people I know and don't see enough of. Many of the people who take the time to give direct feedback are also among those who read this blog. It’s almost like spending time with you. Emotionally speaking, I love that.

People keep asking me (indication of a straw man argument) what they can do to support my efforts as a novelist. First, thanks for asking. It has been a strange book launch. The delta variant has made bookshops worried about planning readings and readers reticent to gather for events.

Even with those challenges, I truly find your good will wonderful. You could take it upon yourself to spread the word far and wide. Consider who you know who might enjoy the book and give them a nudge. Give it as gift over the holidays. If you purchase it in time, arrangements could be made for an inscription. Post it to social media. It is very helpful to write a short review at Bookshop.org, Amazon, Good Reads, or anywhere you may have purchased Half Dead. I have a standing offer to book clubs to Zoom in and answer questions at book gatherings. So far only one such group has taken me up on it. It was fun.

Here is a link to a webpage that will one day be a finished website: BrandonGrahamBooks.com

Thanks.